One might be the loneliest number, but it certainly gets a lot of attention on the SAT. And if it’s been a few years since elementary school, some of this easy stuff might actually be a bit foggy. If it hasn’t been a few years since elementary school, why are you reading this blog? Go play with your sister and let mommy relax.

When I refer to the number one, I’m referring to parts of the number one and the various ways we can designate those parts.

Kickstart Your SAT Prep with Test Geek’s Free SAT Study Guide.

In this post, I’m going to dissect the three main ways the SAT splits up parts of a whole and relationships between two values:

- Ratio problems rely on the relationship between two values (3:2)

- Fraction problems deal with parts of a whole (1/2)

- Percent problems use numbers in terms of their relationship with a whole of 100 (65%)

These three concepts can be thought of as three alternative methods of dealing with one on the SAT math section. If one of these seems to make more intuitive sense than another, the good news is that you can just use that one. Not. Sorry . . . you should assume the SAT math section will somehow read your mind and serve you up a hot dish of the one you hate the most.

SAT Ratio Problems Show Relationships

For every two posts Kylie Jenner makes, she spends three hours counting her new cash. If she makes six posts, how many hours will she have to spend counting moolah?

Okay, that’s a bit crazy. Kylie doesn’t have to touch things. Let’s try again.

For every eight SAT ratio problems you do, you spend two minutes crying. How many SAT ratio problems do you need to do in order to drown in your own tears?

I never said this would be a fun blog, y’all.

SAT ratio problems express the relationship between two values that move together. The ratio is the smallest, most simplified version of this relationship. If you need two parts of blue paint and three parts of yellow paint to make your signature green paint, you can say the ratio of blue:yellow paint is 2:3.

We can take that ratio and figure out all sorts of things. Let’s look at an example:

We are going to do a magic 1-2-3 with SAT ratio problems. This method works with a lot of ratio problems you’ll see on the SAT, so if you are considering a forearm tattoo, it might be worth deciding on a good font for this little guy.

- Figure out the number of total parts. In a 2:3 ratio, there are five total parts (2+3)

- Divide the goal value by the number of total parts. In our problem above, our goal value is 70. This will give us the value of each part. For this problem, every part is “worth” 14 gallons (70/5=14)

- Multiply the value of each part by the number of parts in the desired portion. The question is asking us about blue paint, and our ratio has two blue parts. That means our answer is A, or 28 (14×2=28).

Rather than memorizing these steps, try to understand the process so that it becomes intuitive. Ratios tell us how many parts there are in total. That lets us divvy up the total and figure out how much each part is “worth.” Once we know that, we just multiply based on what the question is asking.

SAT ratio problems are almost always easily solvable if you follow this method.

And guess what? Of the three question types discussed in this blog, I think SAT ratio problems are probably the hardest type. That’s not to say that they’re hard — they’re certainly not. But they are probably a bit more challenging than percent or fraction problems.

There is a type of SAT ratio problem that will require a different method, though. Rather than giving you a ratio and asking you how many ingredients you will need to produce a target value, you will be given a ratio and asked about how many things can be made.

These are essentially limiting factor questions. What’s a limiting factor, you ask?

Imagine you are being chased by bears, but lucky for you, you have some berries and chocolates with you. The catch, however, is that the bears will only pause to eat a berry if there is also a piece of chocolate with it. These are fancy bears.

If you have nine berries and six chocolates, what are you going to run out of first? Chocolates, of course. Chocolates are your limiting factor. You’ll die with three berries and countless unfulfilled dreams.

Let’s take a look at a limiting factor SAT ratio problem:

We have our ratio (6:12:6). To figure out how many glucose molecules we could make, we first need to figure out how many molecules each bit of our “supplies” is good for:

- We have 42 carbon atoms, and we need 6 of them for each molecule. Therefore, we have enough carbon to make 7 glucose molecules (42/6=7)

- We have 73 hydrogen atoms, and we need 12 of them for each molecule. Therefore, we have enough hydrogen to make 6 glucose molecules (73/12=6 point something). Note that “point something” is worth nothing. We either have enough or we don’t.

- We have 41 oxygen atoms, and we need 6 of them for each molecule. Therefore, we have enough oxygen to make 6 glucose molecules (41/6=6 point something).

So, we have enough carbon to make 7 glucose molecules, enough hydrogen to make 6 molecules and enough oxygen to make 6 molecules. Our answer is 6 because our limiting factors (hydrogen and oxygen) can only make 6 glucose molecules. We could have a million hydrogen atoms, but we could still only make 6 glucose molecules.

What would 200 EXTRA POINTS do for you? Boost Your SAT Score with Test Geek SAT prep.

If you can do these two SAT ratio problems, you can probably do any ratio problem you’re likely to see on the SAT.

SAT Fraction Problems

While SAT ratio problems are technically dealing with a relationship between two values rather than parts of a whole, SAT fraction problems are kind of doing both.

Take the fraction 2/3. We have a whole (3) and a given relationship to that whole (2). We can also think of it as parts of a whole where we have two of the three parts.

Fractions don’t have to be less than one, though. The fraction 5/2 means that we have multiple wholes (2.5 to be exact). Fractions like this that are greater than one are often called improper fractions, but this is mostly because of the disinformation campaign by the Big Math Lobbyists™ (please call your Senator, in the name of justice). There’s really nothing improper about them, and as we’ll see in a second, they can actually make life easier.

First, a few quick fraction rules:

- Any number over itself is equal to 1 (5/5=1)

- Any number over 1 is itself (5/1=5)

- Zero over any number is zero (0/5=0)

- Any number over zero is undefined (5/0 is undefined)

That last one can be confusing. Your instinct might be to say that it is 0, but it is not. Think about it this way: How many times does zero go into 5? Is there any number you can multiply by zero to get 5? No, which means this problem can’t have an answer.

There are several things you should be able to do to fractions:

- Reduce

- Add and subtract

- Multiply and Divide

- Convert to Decimals

Reducing Fractions

We often want to have the smallest numbers possible when working with fractions. To get there, we need to reduce both the top and the bottom while keeping the same relationship. To do so, we need to divide by the greatest common factor.

The greatest common factor might bring back bad memories of elementary school, but it’s vital to reducing fractions.

For example, if we have the fraction 4/10, we can see that the greatest common factor (the largest number that will go into both numbers evenly) is 2. Dividing both the top and bottom by 2, we get 2/5, which is our reduced fraction.

Adding and Subtracting Fractions

Before you can add or subtract fractions, you must get a common denominator. In order to do this, we must find the least common multiple. The least common multiple is the sketchy cousin of the greatest common factor. If the greatest common factor is the peacemaker who tries to find the best thing we can all do, the least common multiple tries to see how far we can collectively push things.

But it’s just as easy to find. Here’s my favorite method:

- List out the multiples of the biggest denominator you are working with. If we are trying to add 1/4 and 4/9, we’ll use 9: 9, 18, 27, 36, 45, 54 . . .

- Pick the smallest one that is also a multiple of the other denominator. In this case, the smallest option that is also a denominator of 4 is 36. That’s our least common multiple.

Once we have the least common multiple, we need to adjust our numerators to match. For the fraction 1/4, when we are converting the denominator to 36, we are multiplying the denominator by 9 (36/4=9). Therefore, we must also multiply the numerator by 9, giving us 9/36 as our new fraction.

Once we have both fractions “speaking the same language” with the same denominator, we are going to keep the denominator and add or subtract across the top. 1/4 + 4/9 becomes 9/36 + 16/36, which equals 25/36.

Multiplying and Dividing Fractions

Multiplying and dividing fractions is even easier than adding and subtracting fractions because we don’t need to find a common denominator.

To multiply, we are simply going to multiply across the top and bottom, so 1/2 x 3/4 = 3/8.

To divide, we are going to flip (find the reciprocal) of the divisor (the second term) and multiply. 1/2 divided by 3/4 becomes 1/2 x 4/3 = 4/6.

Converting Fractions to Decimals

This is, by far, the easiest thing you will need to do with fractions. If you are on section four (the calculator section), you can simply divide the numerator by the denominator to convert your fraction to a decimal.

Many calculators can handle fractions, but decimals are often easier to work with if you are doing a lot of work on your calculator.

SAT Fraction Problem Examples

Let’s take a look at a couple examples of how fractions can be tested on the SAT:

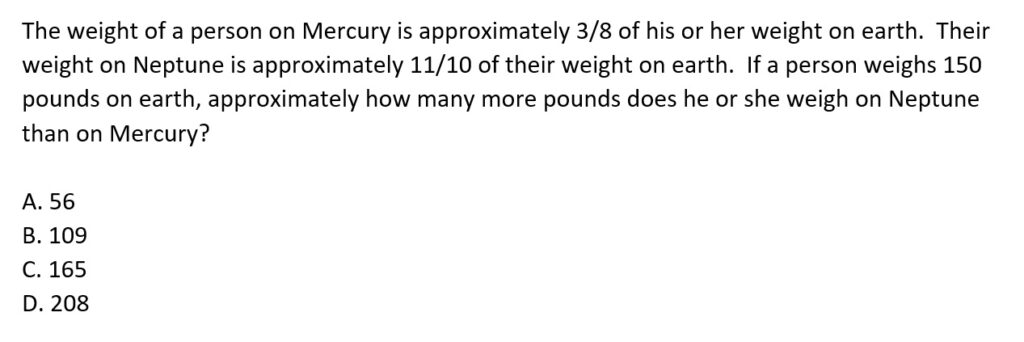

It can be tempting to try to devise some sort of shortcut here, but don’t do it. Instead, just figure out how much this person would weigh on Mercury and how much they would weigh on Venus. Then, subtract.

Once we know the weight of the person on Neptune (165 pounds) and the weight of the person on Mercury (56.25 pounds), we can subtract, giving us approximately 109 pounds, or option B.

Let’s look at another SAT fraction problem:

Assuming you know the basic algebra step of dividing the left side by 3/4 (which is the same as multiplying by 4/3), this is just a fraction multiplication problem:

SAT Percent Problems

Percentages are just another way of expressing parts of a whole. Like fractions, percentages can represent numbers less than one (75%) or greater than one (150%).

You can think of percentages as decimals that are multiplied by 100. For example, .65 is equal to 65% (.65 x 100 = 65).

You will almost certainly see SAT percent problems on the exam. Fortunately, the SAT tends to come back to the same tricks for these problems. The most common types of SAT percent problems you will see are:

- Percentage changes

- Compounding multiple percentages

- Percentages in statistics and modeling

Before we jump into the most common types of SAT percent problems, let’s talk about a few things to watch out for.

First, watch your decimal points. Percentages are expressed as decimals that have been multiplied by 100, and 100 should be thought of as the whole, not 1. This can be confusing, and the mechanics of working through percentage problems can get sloppy if you don’t keep this in mind.

Second, remember that asymmetry exists with 100%. What I mean is that going from 65% to 100% (a 54% increase) is not the same as going from 100% to 135% (a 35% increase), even though both numbers (65 and 135) are equidistant from 100. We’ll talk more about SAT percent problems that deal with percentage change in a second.

Finally, remember that combining percentages means multiplying, but it’s best to use their decimals forms. If there is an 80% chance that event A happens, and a 60% chance that event B happens, there is a 48% chance (.8 x .6 = . 48) that both events happen. It’s much easier to do this math when you convert to decimals first.

SAT Percent Change Problems

A core SAT math concept is percentage change. Let’s say you have a savings account with $100 in it. The SAT might ask what the percentage change would be if that amount grew to $137, or it might ask how much you would have if the account dropped by 18%. You should be able to do either calculation with ease.

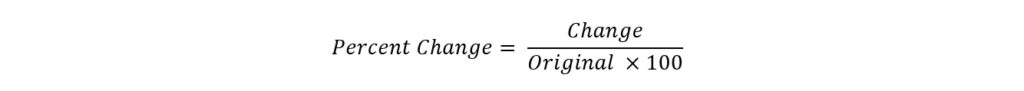

There’s a simple formula for SAT percent change problems:

Keeping that formula in mind, let’s look at an example:

Let me show you a little trick. Many high school math students — even good students — will approach this problem by first figuring out what 70% of $130. They will then add this to $130 to arrive at their answer. While this method will work fine, it is an amateur move.

Don’t be an amateur.

Instead, we can multiply $130 by 1.7! Our whole (the $130) is the “1” portion, and our increase (the 70%) is the “.7” portion. This is quicker, and it saves us from needing to remember values between steps.

130 x 1.7 = 221, so our answer is C.

Compounding Multiple Percentages

Let’s say you just can’t get enough Birkenstock in your life. Like Dwight Schrute, you always have an extra set in your car. You know, for special occassions.

What’s a company to do with a dedicated fan like you? They send you special coupons, of course. So maybe they are having a 20% off everything sale, but they send you an extra-special coupon for an additional 10% off. Do you get 30% off?

Unfortunately, no. Or, as Dwight would say, false.

The reason is that percentage discounts don’t compound that way. Let’s imagine a $100 pair shoes. When you take the first 20% off, the new price is $80 (for amateurs, that’s .2 x 100 = 20, and then 100 – 20 = 80; for non-amateur wannabes, that’s just .8 x 100 = 80).

Your second discount applies to the new, lower price of $80. Taking 10% off of that, you get a total price of $72. That’s a $28 discount from a $100 pair of shoes, and using our percent change formula, we can see that you realized a 28% discount rather than a 30% discount.

The easiest way to combine these sorts of discounts is to think in terms of the decimal that is remaining rather than the portion that is being taken away.

We could do the following:

We are paying 72% of the original amount, which means 28% of the original amount has been discounted.

SAT Percent Problems Using Statistics and Modeling

The SAT math section likes to slide percent problems into statistics and modeling problems. Sometimes these questions might rely on direct percent calculations, but often, they simply require an understanding of percents.

One specific area where you’re likely to see these problems is statistical surveys. I’m not going to detail all of the requirements for a good survey here, but percent problems will often be found in conjunction with survey-related questions.

Let’s take a look:

Don’t get caught up in the numbers. That’s what the SAT wants you to do. At first blush, A, C and D all look pretty good. After all, if you’re just focused on the numbers, it would seem that the majority of fish weigh less than two pounds and 40% weigh more than two pounds. Those are easily-compatible ideas.

But the key is the wording, which is true for many word problems on the SAT, particularly statistical surveys.

“All fish” and “catfish” mean two very different things. The survey is telling us about catfish, so our answer is D.

SAT Ratio, Fraction and Percent Problems: Final Thoughts

Being bad at this stuff is sort of like not being able to make right turns when driving. Being a good driver is about a lot more than just making right turns, but being bad at right turns is enough to make you a bad driver.

You have to be able to deal with parts of a whole on the SAT math section. You should also be able to expand the values of two related quantities, and you should be able to easily move between fractions and percents.

If you found yourself struggling, check out our free SAT prep page, and be sure to review these sorts of problems with the free practice tests found at at the bottom.

Comments